-

-

TOM SCHNEIDER IN CONVERSATION WITH DANIEL MALARKEY

I first saw Tom’s work at the Grinnell College Museum of Art in 2018. It was a solo retrospective curated by Lesley Wright and Donald Doe which completely knocked my socks off. This was a painter who had not sold a painting in so long he had given up painting altogether. He had one painting on his easel from 2012 through 2018. In 2019 we broke the drought and placed two of his works and interest has grown step by step. Most importantly Tom started painting again in early 2020 and is at his easel every day.

Going back 25 years exactly, Tom’s first solo exhibition was at the renowned Phyllis Kind Gallery in Chicago in 1998. Read the New York times Obituary for Phyllis Kind by Roberta Smith if you have not.

While Pop Art was reacting to advertising and pop culture, Chicago Imagism’s pot melted comic books and surreal situations in non-linear fashion. Roberta posits that Leo Castelli (who basically formed Larry Gagosian) had an equal in Phyllis Kind. Phyllis believed in Tom’s work and for this reason alone it is worth taking the time to enter into his universe which is uniquely his own. Tom ended up being my pathway to go back to Karl Wirsum (his teacher), Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson and Roger Brown. More and more collectors are asking for Chicago artists whose careers started in the 60's. There is also a lot of interest in young artists whose stylistic language and content mirrors Chicago imagist artists. Between these two interests, Tom’s work is resoundingly clear and fresh and deserving attention.

In this exhibition Sim Smith is inviting you to discover one of the great artistic voices of Chicago whose voice is solely his own. The future is bright for Tom’s one of a kind universe and a technique that he honed back in 1991.

The interview spliced below I did with Tom in November 2019. I own the artist’s work and live with it at home and it gets better and better day by day. The movement, colours and compositions have a complexity that soothes our fragmented minds and pushes us to an unnatural elevation of our senses thereby transforming our minds for a brief moment, again and again, and then finding ourselves wanting it more and more. — Daniel Malarkey, March 2023

Daniel Malarkey Tell me about studying with Karl Wirsum.

Tom Schneider When I started at the Art Institute, it was always very tenuous for me - tuition. I just wanted to try getting exposed to the most famous teacher as far as an artistic career that I had available to me. I went through everybody's resumes and Karl's was the most impressive. Through my good fortune, Karl was still in his really rebellious stage. He's like the original hippie. We just clicked together really well because of our tendency to be obnoxious in public.

DM And what did he teach you?

TS Just the germ of everything - tends to be a spontaneous thing. And how to build off of your own spontaneity and develop it into something coherent, but only it doesn't have to be coherent to other people. It will be. You have to trust that. But just that you kind of develop your own little dialog. But you could do it every time. A new dialog every time.

I just think it's important. I like impulsive rather than spontaneity. And I kind of think it's the beginning of the creative process, regardless of where your creative process lies.

-

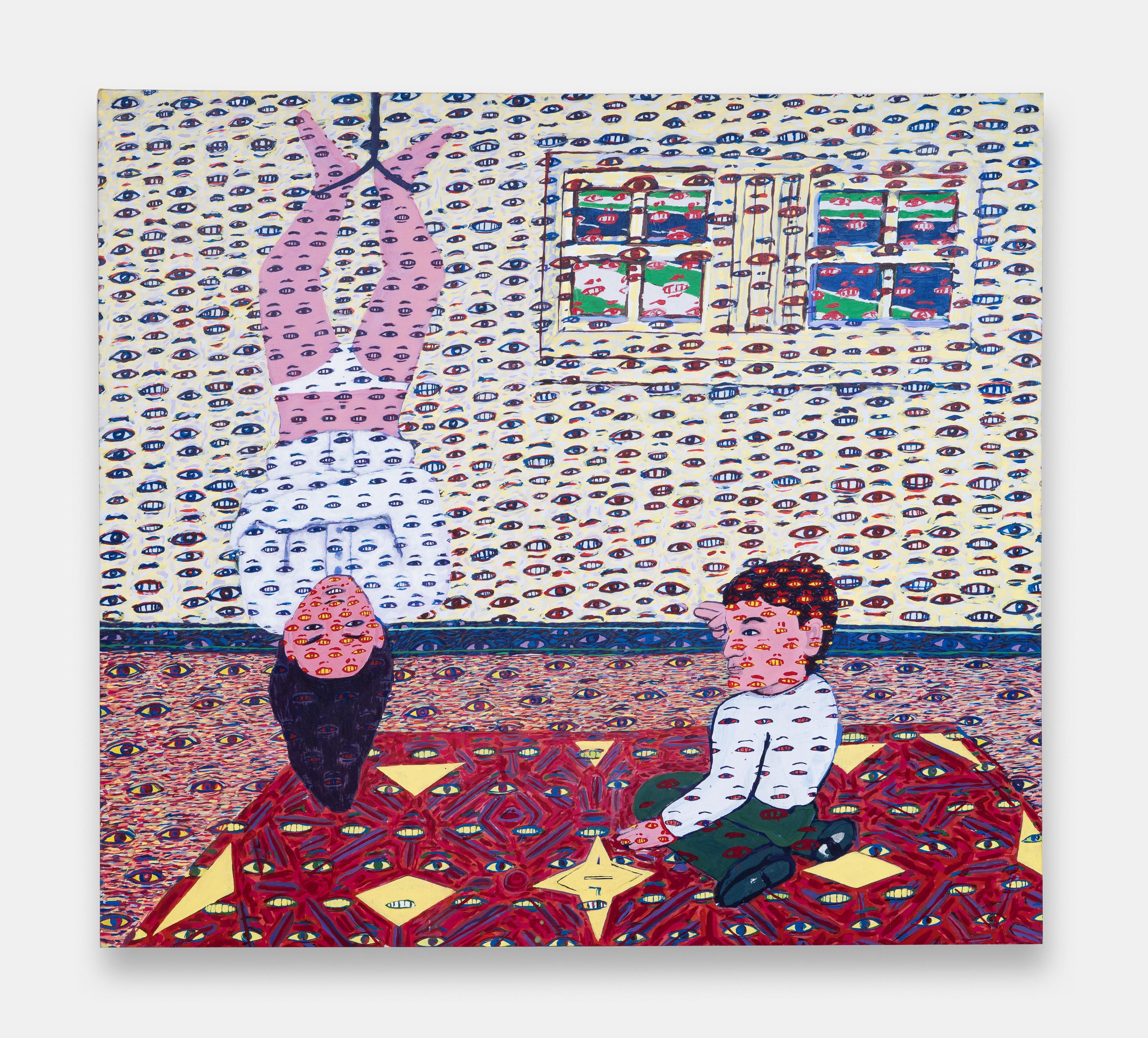

Houdini's Mom, 1991acrylic on canvas112 × 122 cm (44 × 48 in)

Houdini's Mom, 1991acrylic on canvas112 × 122 cm (44 × 48 in) -

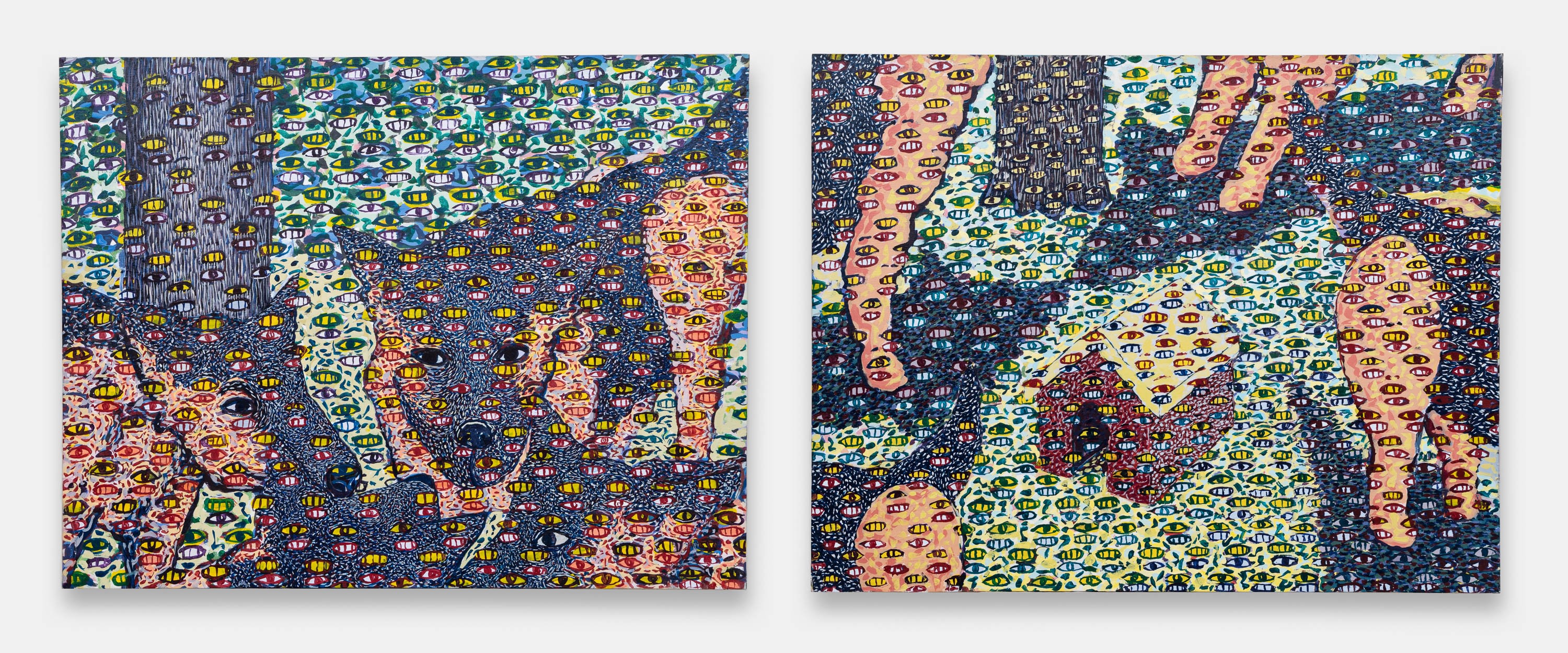

Dogs Setting Upon A Fairy House (Diptych), 1994acrylic on canvas71 × 91.5 cm (each painting) (28 × 36 in)

Dogs Setting Upon A Fairy House (Diptych), 1994acrylic on canvas71 × 91.5 cm (each painting) (28 × 36 in) -

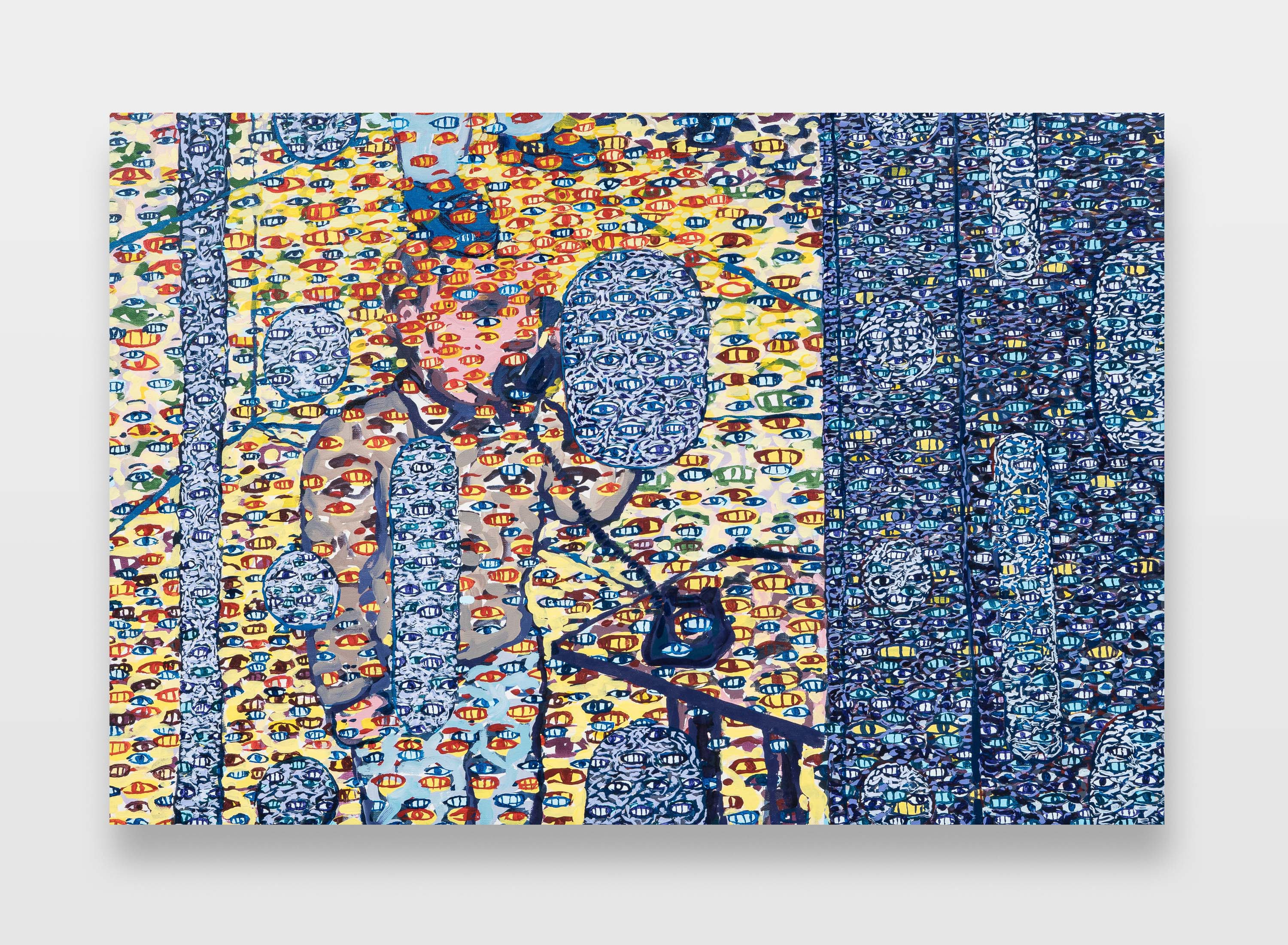

Boy On The Phone, 1994acrylic on canvas76 × 101.5 cm (30 × 40 in)

Boy On The Phone, 1994acrylic on canvas76 × 101.5 cm (30 × 40 in) -

Daniel Malarkey So on that note of your personal vocabulary, when was the first time you started doing eyes and mouths, what you call a checkerboard pattern of eyes and mouths?

Tom Schneider I had a sketchbook. I was at home and I discovered Mexican soap operas. I wasn't so much trying to do the mouth and eyes thing at that point. I just found all their facial expressions so dramatic that I was trying to do these very rapid portraitures off of TV on the quick. The camera angle stopped, and you only have a second to nail that guy's expression or that woman's expression. I ended up with a big stack of portraits. They weren't that great or anything, but it was a really good exercise. And then I'm just like, oh, I can just glue these all together into something else. That's when it dawned on me, I could start lining up the eyes and mouths and all of that. It came out of something completely different. A weird little drawing exercise I was trying to do.

I decided it was all on typing paper, and I had a bunch of that brown paper floating around, and I wanted to do something big because I wasn't showing up to class. And I knew if I brought in a really big and impressive thing, it would make everything cool with everybody. I brought it in for the end of the year critique and put it up on the wall and my teacher and all the other kids in class... it wasn't Karl Wirsum, it was a different person… They were just like, God Tom, this is so cool. And tah-dah, got me out of not showing up to class.

-

Lady Godiva, 1997oil on canvas117 × 137 cm (46 × 54 in)

Lady Godiva, 1997oil on canvas117 × 137 cm (46 × 54 in) -

Naked Possum Juggler, 1998oil on canvas142 × 119 cm (56 × 44 in)

Naked Possum Juggler, 1998oil on canvas142 × 119 cm (56 × 44 in) -

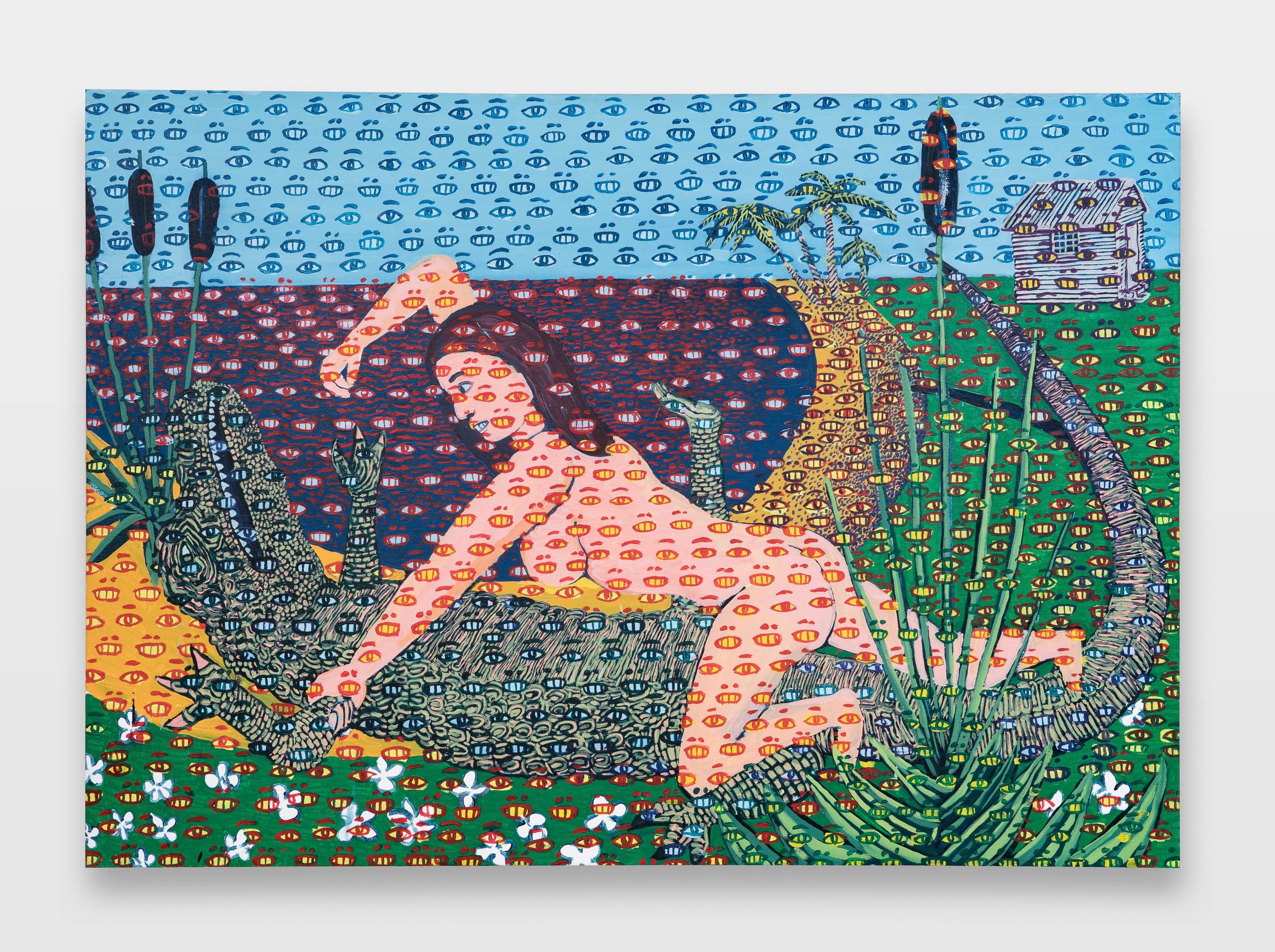

Naked Alligator Wrestling, 1998oil on canvas106.5 × 142 cm (42 × 56 in)

Naked Alligator Wrestling, 1998oil on canvas106.5 × 142 cm (42 × 56 in) -

Giant Squid .vs. A Great White, 2001oil on canvas61 × 76 cm (24 × 30 in)

Giant Squid .vs. A Great White, 2001oil on canvas61 × 76 cm (24 × 30 in) -

Daniel Malarkey How did you come up with the idea of this sort of... invented folklore?

Tom Schneider They are derivatives of other people's folklore. It's just a fresh source of imagery. People write these interesting stories under a journalistic context or whatever reason they get published. Those people are writers and they are not painters. And these stories need to be painted also. Let's put it that way. You know, I want to see it.

DM At the beginning of your career, you were doing works which would be perhaps closer links to a folklore or mythology or story you heard. And then it turned into you coming up with ideas of something that no one else had perhaps thought of, or created a visual to. Could you tell us about that?

TS I got really immersed in all the pulp… it's called Fortean-ism, Charles Fort, and it's all the fantastic stories that people think are true and stuff. Sometimes they start going around in circles, like UFO literature tends to tell the same stories over and over, and there is no reason at all you can't step in there and make it a lot more interesting…as I got older, I don't think you're really obliged to be truthful in your visual imagery. There's not really an obligation.

Painting… art is not real. Art is an illusion. You were talking about making sculpture and stuff. I could never do that. Because sculptures actually exist in three-dimensional reality. It's sort of like literature is so much more because it has a beginning, middle, end. And a painting should fall somewhere within that three act play.

Daniel Malarkey Your scenes are only a moment in time. A snapshot.

Tom Schneider Yes. It should be the best point in the three points. The most interesting point of that story, that play. -

Phone Hex, 1999oil on canvas91.5 × 122 cm (36 × 48 in)

Phone Hex, 1999oil on canvas91.5 × 122 cm (36 × 48 in) -

7 Maidens For The 7-Headed Serpent, 2000oil on canvas106.5 × 122 cm (42 × 48 in)

7 Maidens For The 7-Headed Serpent, 2000oil on canvas106.5 × 122 cm (42 × 48 in) -

Cleopatra Fighting A Lion, 2001oil on canvas76 × 101.5 cm (30 × 40 in)

Cleopatra Fighting A Lion, 2001oil on canvas76 × 101.5 cm (30 × 40 in) -

Daniel Malarkey Ellsworth Kelly said that "painting is somewhere between two and three dimensions. It oscillates between them." What do you think about that?

Tom Schneider I think that's kind of a reference to the non-objective element to art. And I think the artist is trying to talk more about abstract art, than they are just regular straight art. But I think that the whole point of what he called, I think a big component of non-objective art, meaning abstract, or non-representational, is to develop a greater appreciation for the art that's come before it. You see what I mean? I don't think it's rejecting traditional art. I think it's breaking it down. I think it's an analysis of traditional art rather than a rejection of it. There's this quality but, yeah, of course. I find when people start talking in that vein, it's like well if you know how to draw you already know that.

DM It's something that you already know intuitively. Now I saw this exhibition and MUMOK in Vienna on Op Art. And then I was thinking about your art as when I look at the painting my eyes can focus to the eyes and mouths, and then refocus to the scene playing out behind.

TS It's an Op process. Absolutely. I think it has in some pieces stronger than others, but it's not necessarily like a Mondrian is Op Art. It doesn't just overwhelm you. You have to allow a little optic fatigue to happen. So on that level that the Op Art just knocks you across the room if it's done correctly. But I think I'm a little more passive than flat out Op Art. But the process also helps me to stay spontaneous and helps me just go, go, go. It would take me forever to finish. I would get really hung up on how the level of realism achieved without this way of just throwing color in there. -

Dance Of The Nightcrawlers, 2008acrylic on canvas130 × 155 cm (51 × 61 in)

Dance Of The Nightcrawlers, 2008acrylic on canvas130 × 155 cm (51 × 61 in) -

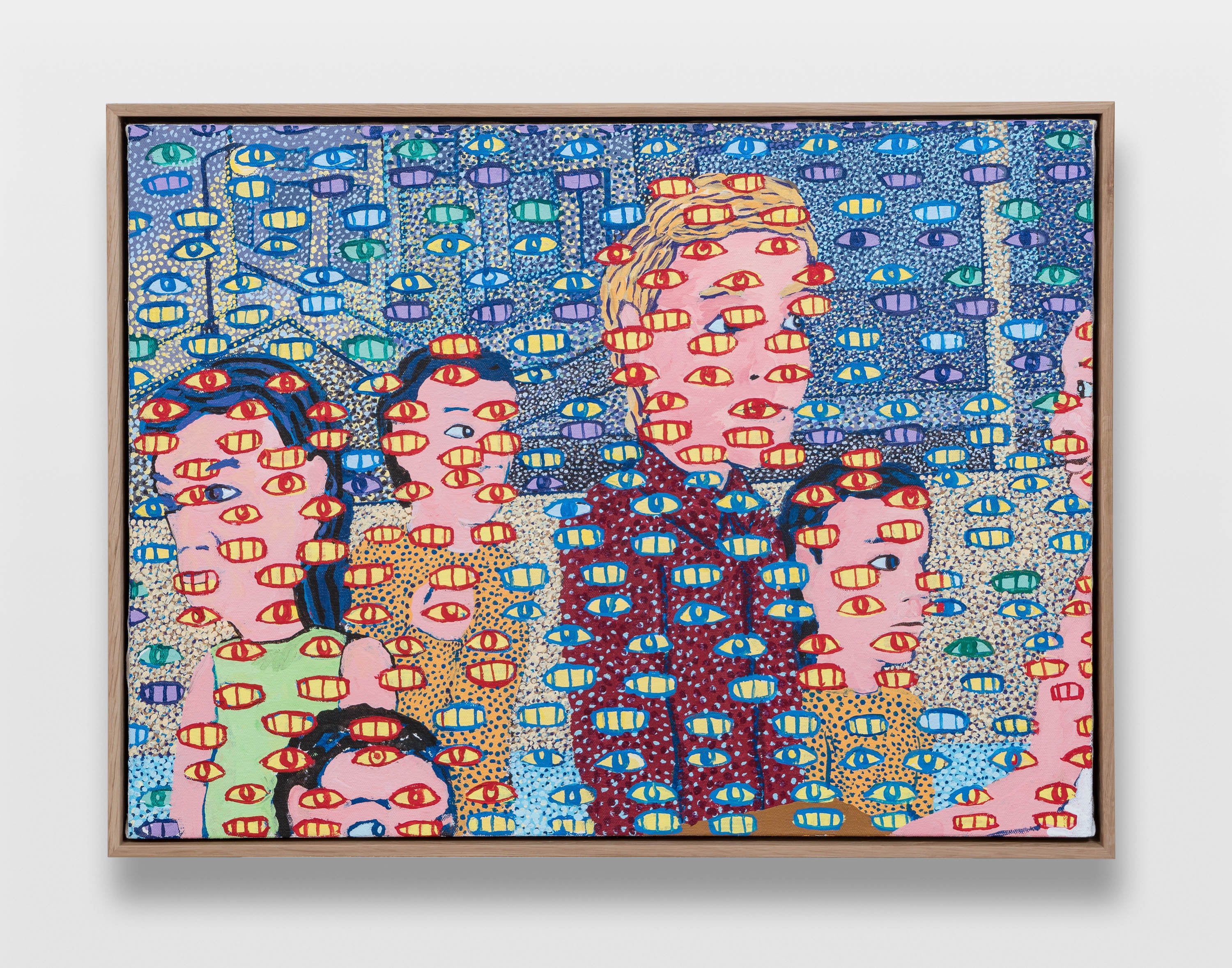

Dining Out Composition 5, 2021acrylic on canvas, wood frame45.5 × 61 cm (18 × 24 in)

Dining Out Composition 5, 2021acrylic on canvas, wood frame45.5 × 61 cm (18 × 24 in) -

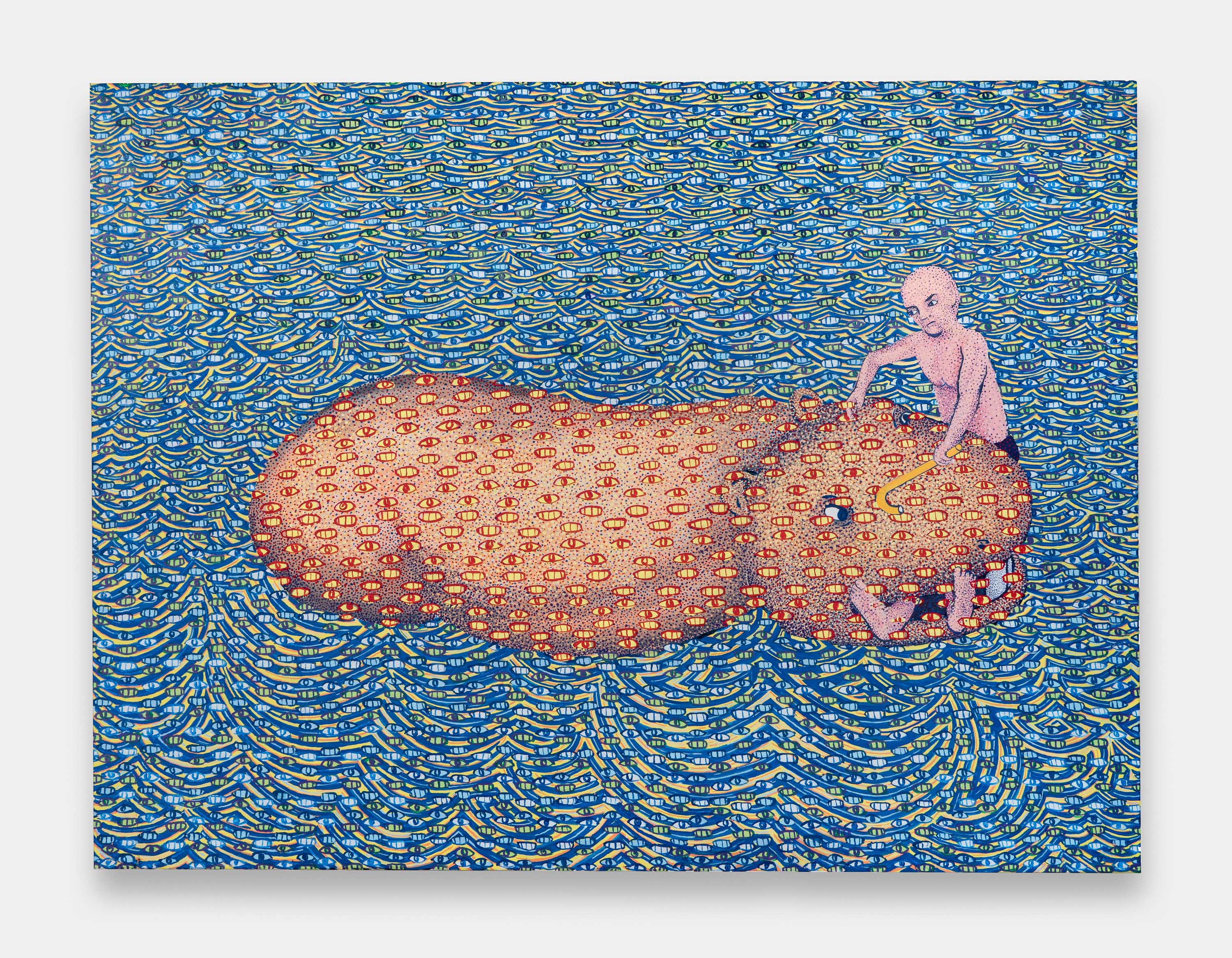

Death by Hippopotamus, 2021acrylic on canvas142 × 183 cm (56 × 72 in)

Death by Hippopotamus, 2021acrylic on canvas142 × 183 cm (56 × 72 in) -

Daniel Malarkey So you talked about reptiles today. There is a building we were at. Tell us about that sort of fantasy that you haven't painted yet.

Tom Schneider Yeah. Yeah. Oh, reptile man and Bigfoot or yetis. They unite and they're taking over my town. I live in Evanston, Illinois. And there's a historic lighthouse with a beautiful old Edwardian mansion attached to the lighthouse. And the idea is that's their home base because they've taken over my city of Evanston, Illinois. And then the winged mermaids with machine guns swoop in and save all of us from these evil doers. It's a complicated story. I can't figure out how to interpret the architecture of my town with the lake and the waves. It's just very, very complicated.

DM That does sound like a very complicated painting. Could it be your largest painting ever? If you do it.

TS I don't know. OK, let's just say I can paint as big as I want. I don't know if I'd go much bigger than what I do now.

DM I'd love to see a huge, huge painting…You haven't done linocut prints for a long time now because you put the printing machine away. Do you think you'll do them again in the future ever?

TS Sure. I mean, if this whole thing comes together where I'm a full-time artist. When you're saying going bigger, I don't think I would want to go bigger with the painting. Some of these paintings are like six and eight feet. I mean, maybe a couple of feet bigger and six to eight feet. The reason I can't go any bigger than that is in this Chicago style bungalow we're sitting in you can't get them up the door now. But I think the biggest prints I have, they're rather elaborate, but I don't think they go much between 23 by about 15 maybe. And I think a bigger one would be really cool. And then we could really be like Bosch. Then you could do a guard and the light thing. Has anyone ever done woodcuts based off of him?

DM I think people have done a lot based off of him. I have to research it.

TS I would love to see like a 17th century woodcut based off of a Bosch.

DM It would be nice to see the visuals in your world where of course one can talk about being a reference his work, but it'll be your own.

TS Yeah, I don't need to mimic the Garden of Earthly Delights. I've got my own.

-

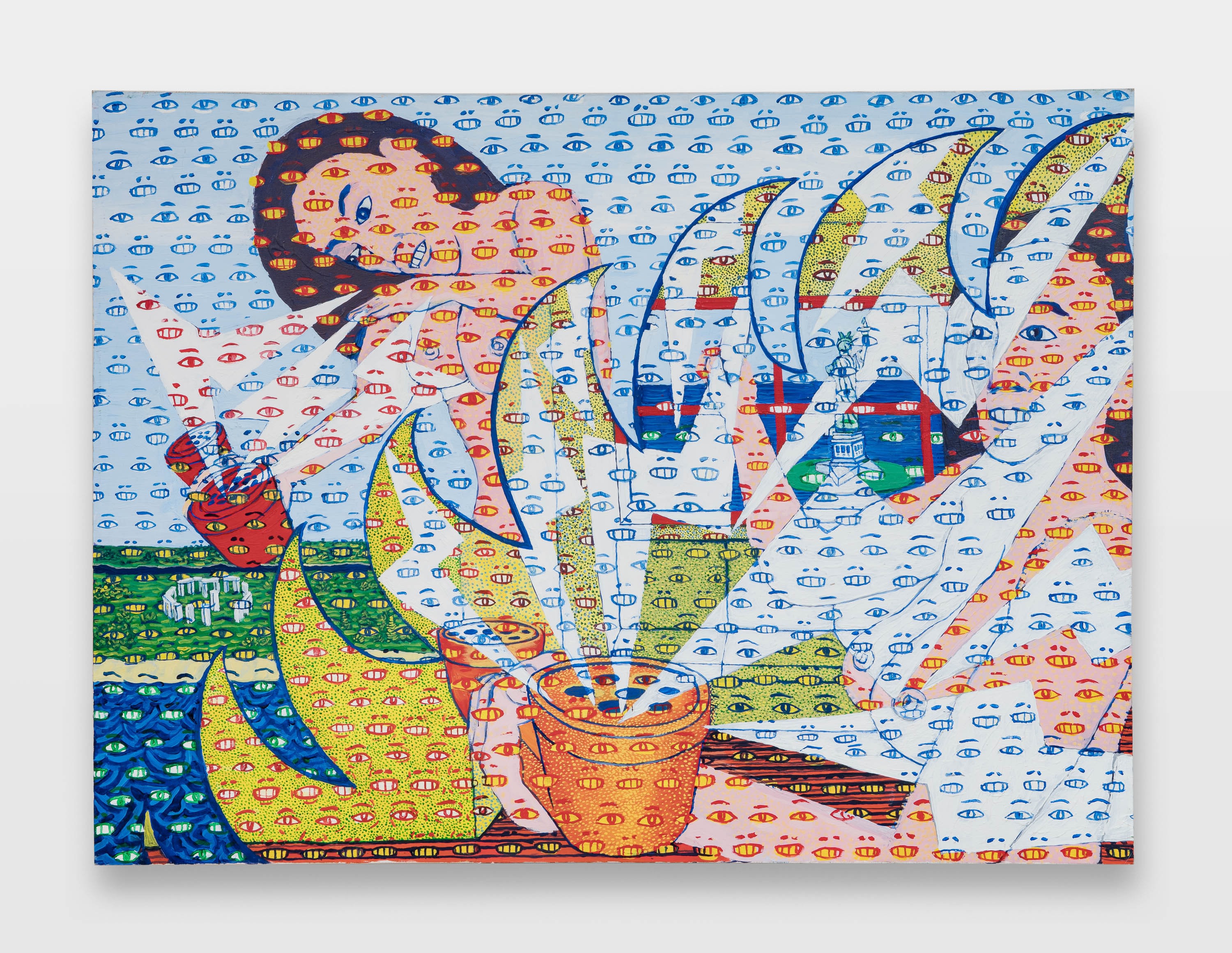

Bikini Girls from Hell, 2022acrylic on canvas119 × 142 cm (44 × 56 in)

Bikini Girls from Hell, 2022acrylic on canvas119 × 142 cm (44 × 56 in) -

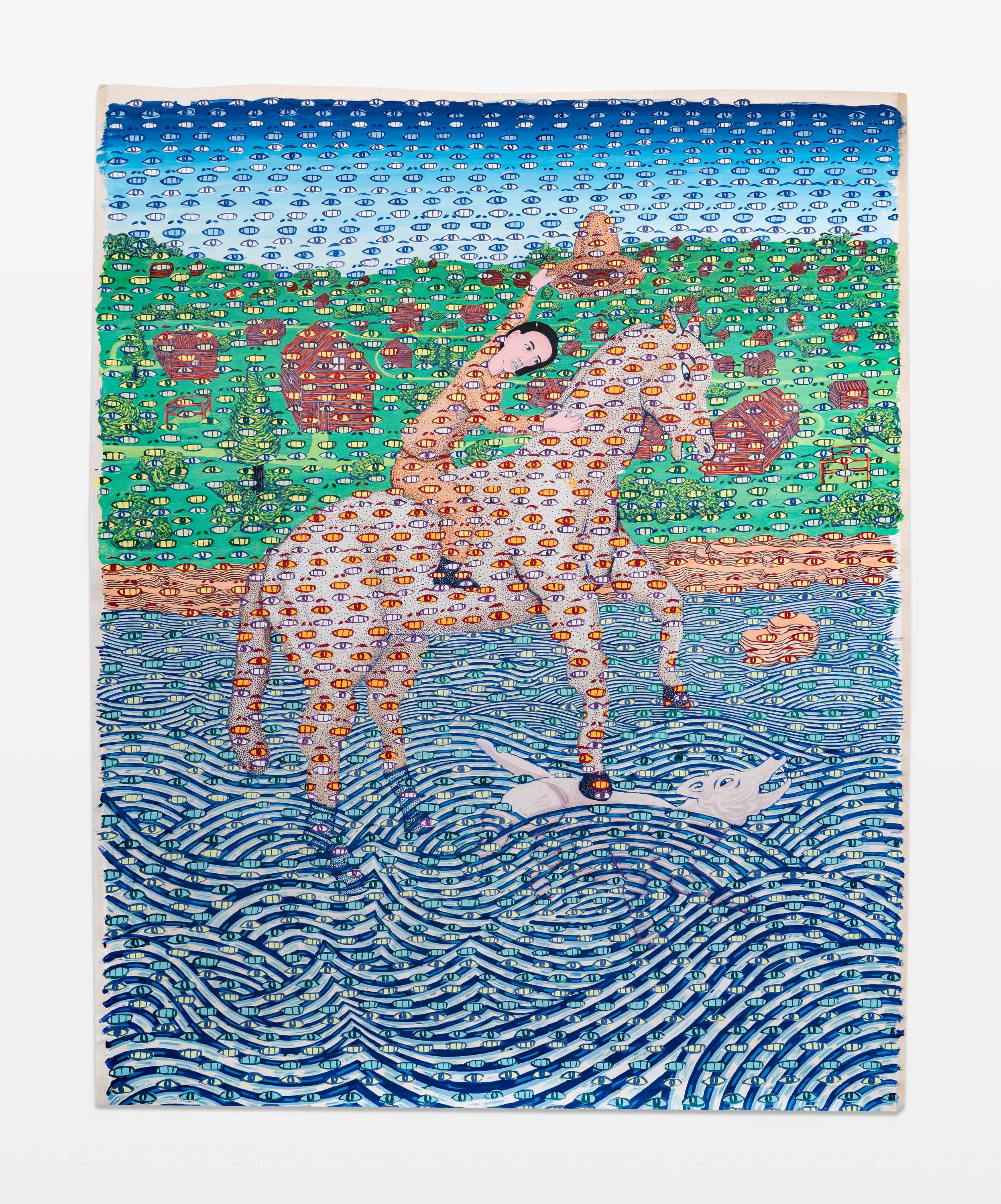

The Trampling Of A Wolf On The Kankakee River, 2011acrylic on canvas178 × 137 cm (70 × 54 in)

The Trampling Of A Wolf On The Kankakee River, 2011acrylic on canvas178 × 137 cm (70 × 54 in) -

Rose Composition 4, 2021acrylic on canvas, colour frame45.5 × 61 cm (18 × 24 in)

Rose Composition 4, 2021acrylic on canvas, colour frame45.5 × 61 cm (18 × 24 in)

TOM SCHNEIDER

Past viewing_room